I'm in the same boat as a lot of others, without a concrete plan for the fall yet, but with schools in my area leaning more and more towards starting remotely. Even if not fully remote, we will be at least hybrid in order to reduce the number of students coming to school at any time so my current plan is to assume remote instruction and to have in-person students join via Zoom to work with at-home students, if we do end up hybrid for some of the time. If conditions improve beyond current expectations, it's a lot easier to roll back and move towards face-to-face instruction than the other way around. This past month of summer break has given me a bit more time time to play around with tech tools, listen to webinars, look at my curriculum, and build on the work I did in the spring in teaching synchronously while remote. This blog post is an attempt to organize some of the work and thinking I've done so far in preparing for next school year. It's pretty long so I have no expectation that others will read, but I need to write out my plans for my own sanity.

As I mentioned in my

previous blog post, I'm working in a small school where all students have school-issued laptops and where classes will be run synchronously via Zoom, which influences the types of instruction I can do, but please don't hesitate to reach out here or on

Twitter if you have any questions for how this might look at your school.

I'm jumping into tech tools first to get them out of the way, but the important stuff is below, my unpacking of the most difficult part of remote learning - students' need for relationships, understanding, and agency.

Tech Tools during Class

The most useful tech tools that I used during class in the spring and that I plan to keep using in the fall were

Desmos Activity Builder,

Classkick, and virtual collaborative whiteboards for breakout rooms. I used Desmos AB and Classkick for students working individually - both platforms allowed me to see students working in real time and to give them feedback via comments in Desmos and by writing directly on their papers in Classkick. Desmos was better for content that involved graphing and making and testing predictions, while Classkick was better for students writing out their steps, working especially well for the small minority of my students who had iPads or tablets and could write with a stylus instead of their trackpad (but it also worked pretty well for kids with laptops only). I remade a number of my lessons as Desmos activities or simply imported pdfs of problems into Classkick. The drawbacks of both of these platforms were that they did not foster collaboration between students, even if I put them in breakout rooms and told them to talk to each other. This was very surprising as students had been used to collaborating effectively in my classes before we went remote so there's clearly something about a remote space that is much less conducive to working easily together. One strategy I plan to use in the fall (as shared by

@mpershan a few days ago) is to assign one student in each breakout room the role of sharing their screen.

Teaching students how to work together in breakout rooms is clearly a new skill and one we'll need to explicitly teach and practice in the fall rather than relying on their face-to-face collaboration skills to just extend into online interactions. I'm considering how to amend structures like group roles and

participation quizzes to work in breakout rooms, since I can no longer observe multiple groups at once. For example, new roles could be: 1. Someone who ensures that a screen is being shared and everyone knows what they're working on, 2. Someone who pauses the room every 5 minutes and checks for understanding and who can call in the teacher if there's a group question 3. Someone who ensures that everyone is writing out their work and there is documentation for the breakout room.

It might be good to shift teacher feedback on collaboration to a peer- or self-assessment model in which students set goals around collaboration, then reflect to themselves or to group members ("in what ways did you contribute to your group today?", "in what way could you be a better group member next time?", "tell your group one thing they did well today" , "give a specific shout-out to a peer who helped you learn today"). A very concrete thing might just be to ask students to track the number of times they asked or answered a question in their group. I think it might also be possible to do an amended form of a participation quiz where I pop into breakout rooms and record what I see in a shared document, although I won't be able to project it to them in real time.

I'm also going to be looking to inject more fun and interactivity into breakout rooms - icebreakers, sharing something non-academic, Anne's

concentric circles activity, something small that gets kids talking and sharing their screens and builds their comfort level with digital participation. In whole class discussions, using the chat feature of Zoom (set to "chat to host only") was incredibly helpful in drawing in shy students in the spring and I will continue using it to invite more participation and to get insights into kid thinking in real time.

In the spring, I also used virtual whiteboards quite a bit when I wanted kids to work on novel problems together or to go over homework questions. I bounced around a few different ones - assigning a page in

Jamboard or a slide in a shared Google slideshow per group were great for students adding photos of their handwritten work and incorporating typed comments, but not great for handwriting.

Bitpaper was best for writing and graphing math, but unfortunately, due to increasing use, they removed their free version for new users a few months ago (if you made an account before this and had some boards, you can keep using these for free, which is what I'm doing).

GoBoard is probably my second favorite for writing out math work and has handy integrations with Desmos and LaTeX. If you have some money to spend, either Bitpaper or

Ziteboard work really well for writing out math work and integrating photos of work on paper with handwriting and typing on a computer. If not, Jamboard and GoBoard are decent options.

Online whiteboards are going to be a big part of my remote plan this year as well, and I need to also be explicit about norms there - the role of writer should rotate, everyone works on the same problem, students should look for multiple methods or connections between problems, there should be a check for understanding before moving on to the next problem, work must be clear enough that someone not in the group could understand your process. As these will be largely used in breakout rooms, these norms will need to be incorporated with the breakout room participation norms. So! Many! Norms! I will have to be very intentional about rolling these out sequentially and creating a small enough list that won't overwhelm students. But I know that time invested up front in fostering effective group work will pay huge dividends in how well students are able to learn from each other and work productively together for the rest of the year in a remote environment.

The big new tech thing that I plan to use in the fall is

OneNote digital class notebooks. There was a pretty steep learning curve to figure out how they work from the teacher side, but I think they're now ready to go for the start of school and should greatly simplify the coordination of classwork and homework, as well as giving easy feedback to students in real time so that I may no longer need tools like Classkick or Google Classroom to organize assignments and feedback. It also means that I'll want to build in some time at the end of class for students to take photos of their handwritten and Desmos or whiteboard work to insert into their digital class notebook and reflect briefly on their understanding. One of my big takeaways from the spring was that everything takes 50% longer when teaching a class remotely, but it is also documented more thoroughly. There is potential here for deeper learning, but I will have to account for the amount of time that things take and be focused on the most essential topics in the curriculum.

It might also be helpful to state that I'm not planning on investing a lot of time and energy into making content videos. I have provided curated

video resources for students in every class for several years now and based on student feedback and my own priorities, I'm going to continue outsourcing this. I don't think it's worth it for me to record a lot of videos teaching math content when there are already so many out there, many made by people with way better video recording technology and know-how. In the spring, I did often make short videos in response to student questions or common errors on their work, and I will make these as needed again this year, using the Notability app for iPad and iPad's native screen capture or by recording a Zoom call with just myself in it and screen sharing from my iPad so that my face is also in the video. But these videos are going to be in response to student work, not a replacement for synchronous class time.

Relationships/Communication/Support

I'm thinking a lot about teacher-student as well as student-student relationships for the coming year and while I list out individual ideas below, I know that a conversation with my department and school about values and priorities is going to be the most important. We need to plan out how to care for students remotely, how to know how they are doing and what we can do to support them as students, but also as kids and people who are lonely, bored, scared, and disconnected from their normal support networks.

I loved a suggestion from

Audrey around students sending her photos of things that have meaning for them (sounds like pets were a crowd pleaser) and starting each class with a student talking about that photo. She then compiled all of the photos for an end-of-year slideshow. Several others have also proposed converting Sara VanDerWerf's

Name Tents, which is how I usually start the school year, into a digital form where students respond to prompts either in writing or via short

Flipgrid videos. Teachers and students could respond to these with their own videos. This also made me reflect on the power of audio or video feedback to foster teacher-student relationships as this was something mentioned by several teachers who regularly teach online. I'm excited that OneNote will allow me to easily record an audio response to student work. I had been planning to use

Voicethread to do this before I committed to OneNote, but I know that students really appreciated video responses to their work in the spring and that they help to humanize what could otherwise feel like dry content-focused interactions.

Another idea that I liked that was shared this morning in response to

Julie's post on teaching in a hybrid model (in which students are split into two groups and each week, they rotate which group is at school and which group is at home) was assigning each student in a group a buddy in the other group who could help them know what was going on during class or let the teacher know if there were issues when their buddy was learning from home. In the spring, I used

Padlet for students to post and answer each others' homework questions and ran an after school homework help time over Zoom where students could drop in and work with peers and math teachers for a few hours each week. I will continue using Padlet and running after school Math Lab, but am also considering other outside-of-class structures that might encourage more interactions between students. Study groups? More group projects? This is an area where I could really use the wisdom of the collective - how are others planning to foster student-student relationships in their schools?

One of the things I took away from a

"Designing for Online Learning" course I completed at the start of the summer from Global Online Academy is the importance of clearly organized course materials and easy to access supports for students. I used a Google Site in the spring with a daily agenda so that students could easily follow the sequence of a lesson and know what was going if their audio or video cut out or they lost their Zoom connection. Moving to OneNote will make it easier to share monthly, weekly, and daily plans with students so that they have a clear understanding of the content goals and work they are completing.

I am also going to cycle in

one-on-one conferences with students to find out how things are going, build relationships, set goals, and go over feedback together. I conferenced with the majority of my students in the spring and although it was a lot of time and work to set up, I felt that they were incredibly worthwhile, even more so in a remote setting than in face-to-face school. My students benefited, but I also benefited tremendously in my ability to empathize and support specific students. In my experience, making these meetings required and ongoing (once a month is a good frequency, I've found) is key. My school will also be setting aside one day each week for tutorial slots so those will also be great opportunities for students to access support. I will also continue seeking feedback from students on how things are going and using that feedback to correct course. Short, anonymous student surveys once or twice each semester, rather than an end-of-year longer survey, have been more helpful for me in getting actionable feedback. Relationships and timely feedback were critical in the spring for motivating students to show up to class, engage with content, and reach out for support, and I know they will be even more so with a new crop of students who don't know me or each other very well yet.

Curriculum

My biggest content take-away from the spring was the importance of student agency in motivating students to stay engaged and work remotely, without the norms of being inside a school building. I built

choice into assignments, I let students select their own breakout rooms every few class periods and let me know how they would like to work during class, and I designed the

end-of-semester projects to have options and to include a variety of student interests. Student choice to support differentiation is something that's been important to me for a long time and I

presented on it this summer, but in a remote environment, I need to be way more organized with helping students set goals, receive timely feedback, and revise. I've done a bunch of curriculum work this summer to hopefully be in a place where more of my time is spent giving feedback and conferencing with students and less on writing problem sets and planning lessons. And I'm hoping that OneNote is a platform that supports organization of assignments, quick feedback, and revisions.

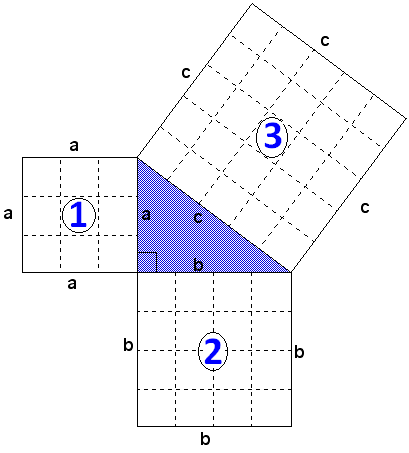

With respect to deepening the curriculum, I've also revised several projects to include more choice and to bring an anti-racist lens to student mathematical thinking. For example, the first 8th grade project for the last several years has been to find a proof of the Pythagorean Theorem from the many options available and present it to the class.

The revised project will include more of a humanistic look at how different cultures have used and thought about this right triangle relationship and why it is that we have named it after a Greek mathematician instead of the many others who also explored it. Students will learn more context and history of the mathematician whose proof they are presenting and the work of non-majority culture mathematicians will be celebrated. A key understanding for this project this year will be to critically examine who gets the credit for a mathematical idea and how different cultures come to understand, apply, and prove mathematical ideas. Two later projects (one on modeling data and one on using concepts of standard deviation and z-scores to analyze outliers) will have a social justice lens this year - students will still have choice in their research questions, but will be working within the realm of social justice topics.

I will also be focusing more explicitly on retention this year since learning remotely may really impact how deeply students are learning content and there may be more gaps from last spring. Working on a curriculum team this summer, we revised the standards for 8th grade to more explicitly connect back to earlier content and we've rewritten homework problem sets to spiral in previous topics. Sara VanDerWerf has blogged about her

use of green reference sheets to better support students with gaps in prior knowledge and I plan to use a form of this as well, since we already start each unit with a pre-assessment to help us and students know what topics in the upcoming unit will need the most support. I've been incorporating an

"Important Concepts" section into notes packets, but am still thinking about how to best use this with students. Should students be creating their unit summary page? Should there be more explicit use of teacher-made reviews and references throughout each unit? Since many class periods are structured around problem-solving and student-led exploration, with some time spent synthesizing and applying at the end, rolling out a summary of what students will learn ahead of time seems detrimental to that process. At the same time, many middle school students are not great note-takers and having a clear summary that can help them see the big picture or review and solidify what they explored in class seems like a good idea. I'm going to play around with summary structures this year that build off student thinking and will hopefully, have more to report on this soon. I'd love others' input on how they've integrated review and content summaries with problem-based learning.